| More than five years have passed since former astronaut Capt. James Lovell delivered a note of pessimism at a speech to BYU students. “I’m not sure what the future of manned flight for this country is,” he said. “I think we’re going to be losing a lot of prestige and be sort of considered as a second-rate space country, but that’s my opinion.” Indeed, that was the mood back then as the space shuttle program came to an end and U.S. |

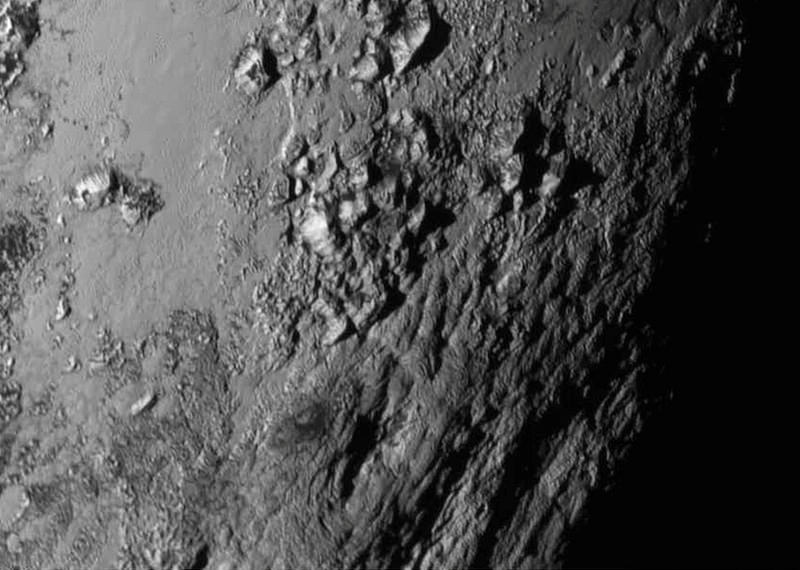

| | astronauts were relegated to hitching rides on Russian rockets — an unthinkable situation for a nation that proudly left its flag on the moon only 40 or so years earlier. So it was gratifying to see that prestige rocket back to first-rate Tuesday when the first close-up photos of the dwarf planet Pluto came down to earth. For the first time in years, I felt some of the excitement I remember from the Apollo days of my youth. It turns out we don’t need actual humans in space to capture human imagination. And while that may be surprising, we should be used to things like that by now. The joy of space exploration always has been the surprises it brings. We tend to get a little mixed up about that. From the beginning, the idea of leaving earth’s bounds has been miscast as a matter primarily associated with national security. That aspect is important, of course. Mankind rarely has conquered new realms without eventually incorporating them into its struggles for survival and supremacy. But you may laugh to learn that the day after the Soviets launched the first man-made satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, U.S. military experts declared it useless because it was impossible to drop bombs from outer space. It’s easy to see that as absurd from the point of view of a world in which, among other things, joggers track their distance and speed using watches connected to satellites, many Americans carry devices in their pockets that can transmit pictures and video instantly across vast distances, Google Earth and other navigation tools keep vacationers from getting lost, and medical devices and procedures exceed anything predicted in 1957, all the result of space exploration. The lesson is that leaving planet earth always has been more about discovering answers to questions we haven’t yet thought to ask than about claiming new territory for the motherland. The New Horizons spacecraft’s close encounter with Pluto ought to make us all wonder what new things we might yet discover or invent. And yet the close encounter with Pluto is unmistakably an American moment. Perhaps it isn’t on the same dramatic scale as Neil Armstrong hopping from a ladder to the surface of the moon, but it comes darned close. As NASA administrator Charles Bolden and presidential science and technology assistant John Holdren wrote in an op-ed published by the Baltimore Sun, the mission means, “the United States will have visited every planet and dwarf planet in our solar system, a remarkable accomplishment that no other nation can match.” Not only that, the scientists involved in this mission set New Horizons on a path in 2006 that brought it to this point, 3.6 billion miles from earth, and gave it the capability to maneuver and transmit detailed photos back to earth. That is no small feat, and while perhaps not a giant leap for mankind, it means the nation has, at least temporarily, gotten its space legs again. Who knows how long the feeling will last. Despite recommending an $18.5 billion budget for NASA, President Obama has not made space exploration a priority. A manned mission to Mars remains a distant dream — something predicted for the mid 2030s or beyond. The United States always will struggle with the enormous cost of space exploration, juxtaposed against other priorities and an ever-growing national debt. It’s hard to fund a nation’s imagination, regardless of how well that has paid off in the past. Still, it was nice to see one of Lovell’s fellow former astronauts, Buzz Aldrin, tweeting on Tuesday, “The #PlutoFlyby helps reflect inward about its influence to embark outward from Earth with human exploration settlements into the universe.” It’s good to see those old pioneers being optimistic again. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed