| You don’t have to search far on the Internet to find budget games that let you try your hand at setting the nation on a sustainable fiscal course. The underlying message is always the same — it ain’t easy, especially if you are a rigid political ideologue. And who isn’t, these days? The problem isn’t so much that your choices on Tuesday’s ballot are between candidates who promise never to raise taxes and those who promise never to cut entitlements — although this |

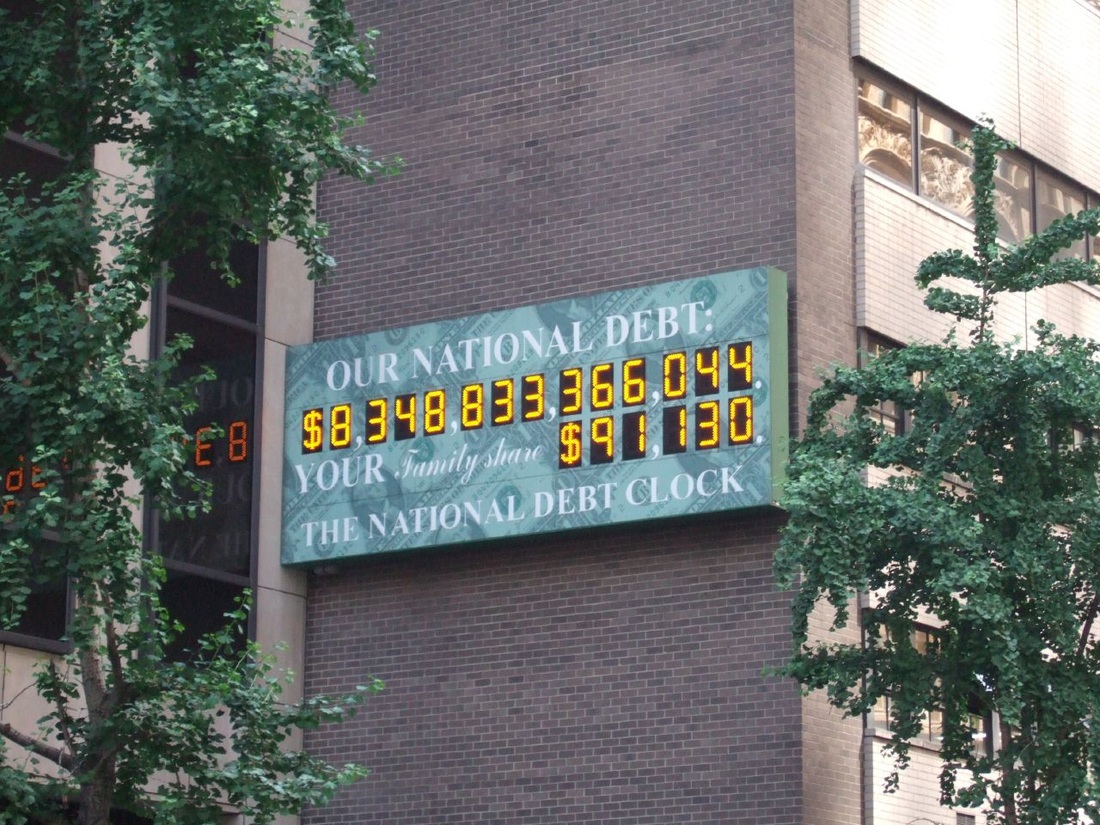

| | essentially is true. It is that no one is even talking about the problem. These days, the halls of Washington seem filled with the fiscal equivalents of alcoholics who, so long as they continue to function reasonably well in society, have the luxury of denying they have a serious problem. After all, no one knows which drink will be the one that tips the scales in the wrong direction. It probably won’t be the next one, so, bartender! And no one really knows how high the national debt has to go as a percentage of the economy before things start to fall apart. Some experts say 90 percent. Others maybe as high as 120 percent, in which case we have a little time; maybe even a few more elections. In the meantime, unemployment is down, inflation is almost zero; we pay about the same for gas (adjusted for inflation) as we did in 1965. Why worry? When moderator Chris Wallace finally asked a question about the debt during the third debate, both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton gave vague and general answers. Trump promised to add “tremendous jobs” to the economy, cutting taxes and fueling an economic growth of up to 6 percent annually. Clinton said she wouldn’t add a cent to the national debt, paying for her programs by socking it to the rich. Analysts haven’t taken too kindly to those answers. Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said Trump’s projections are unlikely, given that the nation hasn’t seen anything approaching an even 4 percent growth rate since the booming ‘90s. And Clinton’s plan might pay for her new programs, but it wouldn’t reduce the national debt by a cent, either. As the Brookings Institution’s Ron Haskins put it, “In other words, Trump would make the debt problem worse and Clinton does nothing to address the debt problem.” He also said the nation’s debt trajectory isn’t likely to change because no one is in the mood to compromise and, “Not only are severe consequences unlikely to occur in the next few years, no one can predict when they will occur.” Few people like uncertainty, so let’s stick to the things we know. The Congressional Budget Office says the current debt equals about 77 percent of the gross domestic product and is rising. At some point, this will result in higher interest rates and lower wages, which will stunt economic growth. If it gets bad enough, the people investing in our debt will begin to fear the nation’s ability to repay and will demand a higher rate of return, which means higher inflation and slower growth. One other thing is certain: It’s easier to fix this now than it will be when the crisis hits, just as it’s easier to join a recovery program today than to wait for the drink that ruins your liver or that makes you wander the streets talking to yourself. Not that fixing things today would be easy. I finally decided to play a budget game posted by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, but I wasn’t very good. I reformed Social Security by raising the age for eligibility and cutting benefits to the rich, but I didn’t want to cut the military or homeland security in these troubled times, and I wavered on raising my own taxes. The game said I needed to cut about $2 trillion more to get the debt to less than 60 percent of GDP by 2024. To do that, I would have to get ruthless. That’s hard work. I’ll have to fill up with some cheap gas and drive around a bit while I think about it. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed