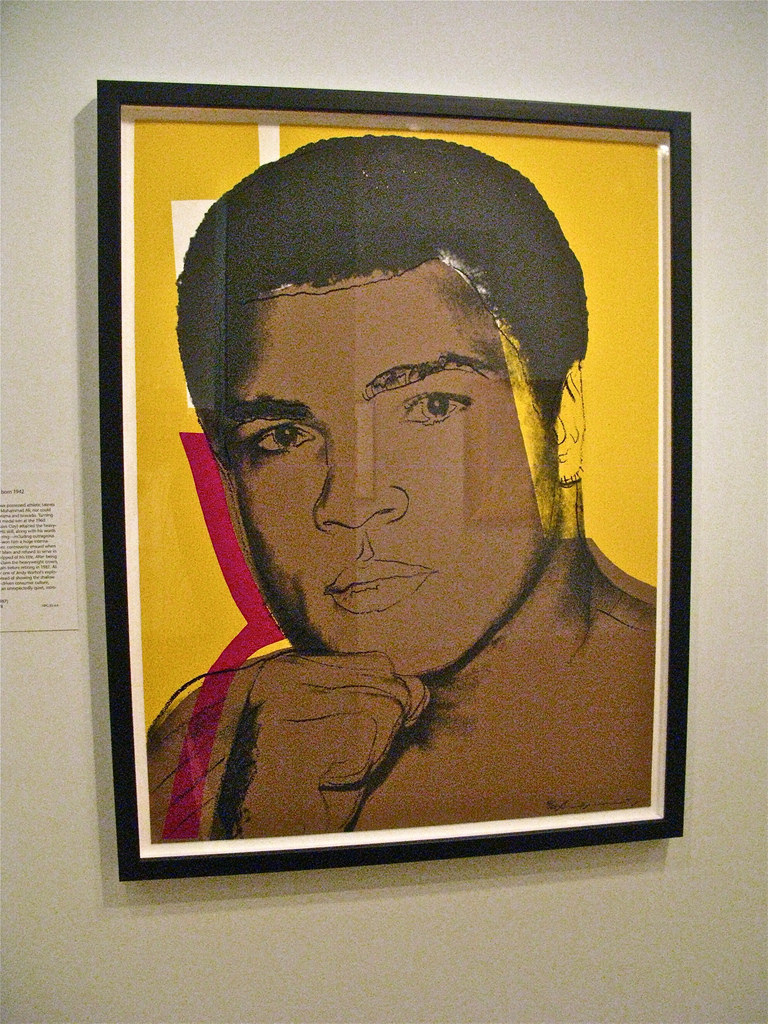

| When I came to Utah in the mid-1980s, friends in Las Vegas, where I had worked as a reporter, warned me things would be dull here by comparison. But then I must have slipped through some sort of looking glass at the state border, because suddenly I thought I saw Muhammad Ali walking the streets of Salt Lake City campaigning for the re-election of Sen. Orrin Hatch. It was the summer of 1988, and Hatch was running against Brian Moss, the son of three-term Senator Frank Moss, who Hatch had unseated in 1976. It might have been as dull a race as my friends had predicted, except for the former heavyweight champ holding court with the media, saying things like, “This Brian Moss, he’s no match, for a great statesman like Orrin Hatch,” or, as he told Hatch at a press conference, “Tell Moss you’re the boss.” Vegas never was like this. Down there, the mud flew fairly thick during election season. But it was a |

| | garden-variety mud, with predictable barbs and insults. This was something else entirely and, as it turned out, it was a one-time oddity in Utah’s political history. Ali’s death over the weekend brought it all back, just as it brought back so much else in the complicated, and ultimately inspiring life of a great boxer. I’m old enough to remember a time when the thought of Ali as an example of civility and humanitarianism would have been absurd. Until he came along in the mid-‘60s, athletes were expected to be gentlemen, at least outwardly. When football players made it to the end zone, they politely tossed the ball to the referee. NBA players seldom dunked, afraid to appear to be showing up their opponents. And boxers typically said they respected their opponents and wished them luck. Then along came Ali. Go to Youtube and watch a video of the weigh-in before his fight with Sonny Liston, the reigning champ at the time. The backstory is that Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, had just spoken at a rally of the Nation of Islam. Many people saw him as dangerous and radical in more ways than one. Ali was in a frenzy at the weigh-in, boasting about himself. But people are complicated. Ali, it turned out, was a genius at showmanship and psychology. As he said later, "Liston's not afraid of me, but he's afraid of a nut." He also was sincere about his religious conviction, as became evident when he refused to fight in Vietnam, even though it put his career in jeopardy. Sincerity ultimately defined him, as well as a sense of humility. It would have been just as absurd in 1964 to think of Ali as a supporter of a white, conservative Republican from Utah. But Ali never cared much what others thought. He apparently made his decisions based on deep-seated values, not personal gain. In some ways, Ali was riding on the crest of a growing wave in 1964. Fifty-two years later, being a brash braggart is the norm in public life. Football players dance in the end zone, basketball players pound their chests and taunt their opponents, and boxers call each other names. And this year, even some national politicians have surrendered the pretenses of decorum. As a psychological tactic, taunting has lost its edge. We are growing less and less afraid of a nut. And yet the nobler side of Ali’s character, the one that rightly earned him adulation and respect later in life, is viewed almost as an eccentricity. As amusing as Ali’s visit was in 1988, he was not mean against Hatch’s opponent. He also wasn’t partisan. He supported some Democrats that year, as well. He liked Hatch in part because the Utahn helped one of Ali’s friends get a job in the Justice Department, and he felt a sense of loyalty — a sense that grew into a lasting friendship. Loyalty, decorum, religious conviction and political sincerity — all things many saw Ali threatening in 1964 — ended up being the traits that made him an enduring figure. If only that part of his life rode on the crest of wave, as well. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed