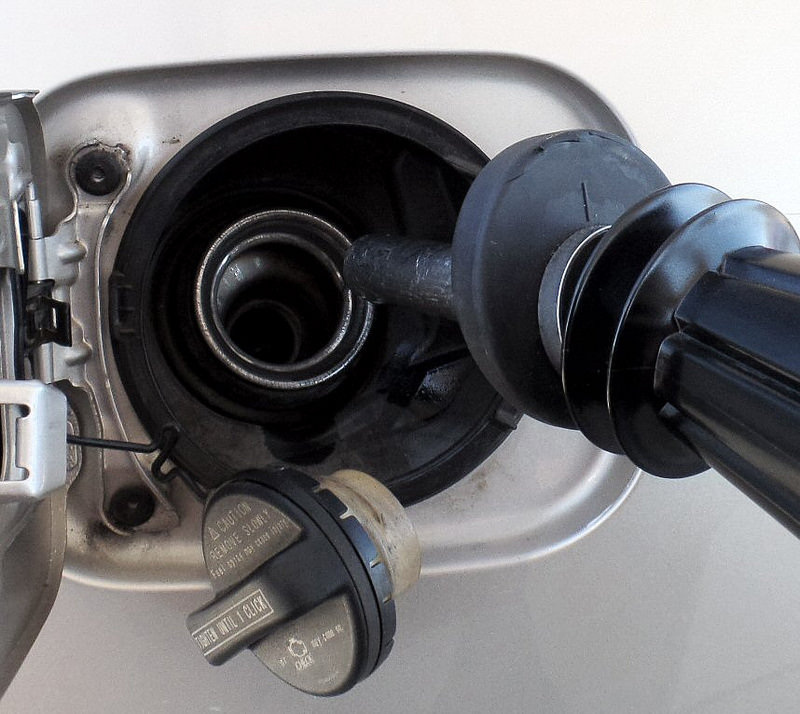

| Are you ready to open wide and swallow a tax increase? After all, it will be good for you. At least that’s what we’re being told. Utah, according to the experts, faces an $11.3 billion transportation shortfall between now and 2040, and we had better start paying now. But don’t close your mouth and walk away yet. Once you’ve swallowed a Utah gas tax increase, you may have to fill your spoon with a federal one, as well. As a Wall Street Journal editorial put it recently, falling gas prices “are the first lucky break for U.S. |

| | consumers in years,” but politicians of both major parties see it as an opportunity to pull a few more dollars out of the economy. And because Americans deal with several sets of politicians on local, state and national levels, they can be assaulted repeatedly by a series of increases on all those levels. But if more money is needed, and there are compelling arguments that suggest this is true, then it should not be too much to ask that it be extracted in ways both efficient and accountable. In Utah, so far, such a plan has yet to emerge, with one small exception. A portion of HB362, sponsored by Rep. Johnny Anderson, R-Taylorsville, would allow counties to raise general sales taxes by 0.25 percent to fund transportation needs, such as roads that are paid for and maintained by those governments. A sales tax would indeed be accountable, because it would require a public vote. It would not, however, be a true user fee, although it may be assumed that anyone making a purchase at a store must have driven there on a road. Nor would it be completely fair. Someone who drives down the street to buy an expensive sofa would pay considerably more for the upkeep of that road than someone going for a gallon of milk. But it’s hard to devise a truly efficient system using traditional taxes. The rest of Anderson’s bill would turn the state’s gas tax into a type of sales tax based on the average price per gallon during the previous year. The yearly calibration is a way to keep highway revenues from fluctuating wildly with the price of gas. However, you may rest assured that a year such as this, in which prices have dropped by about 40 percent, still would add a touch of the wild side to transportation funds. When it comes to gas taxes, efficiency can be as elusive as runaway mercury. Merely raising the gas tax does not do it. Over time, inflation eats away at that money. And as cars become more fuel-efficient and people buy more hybrids, the tax becomes even less effective. And yet this seems to be the direction Utah lawmakers are heading as the session rapidly approaches its deadline. The Senate prefers a 10-cent increase per gallon. The House seems willing to compromise on 5 cents, if it also can get a version of Anderson’s yearly-adjusted percentage and the local sales tax. As I’ve said before, the fairest and most efficient solution would be to abolish the gas tax entirely and set up a system of variable tolls on major highways, which would increase when traffic is congested and decrease considerably when traffic flows freely. This would have the added advantage of incentivizing people to drive at off-peak times, which would reduce air pollution. But there is little political will for such a solution, or for much of anything beyond variations on the old ways of thinking. Nor is there much will in Washington to do as the Wall Street Journal suggests and greatly reduce or abolish the federal gas tax in order to allow states to raise more money without hurting taxpayers. On Tuesday, a transportation research group known as TRIP released a study showing, in detail, the many highway and transit needs the state will face as its population grows. Governments do indeed have a responsibility to keep people and commerce flowing smoothly. It would be nice, however, if they could do in creative and efficient ways that don’t abruptly end this pleasant period of low gas prices |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed