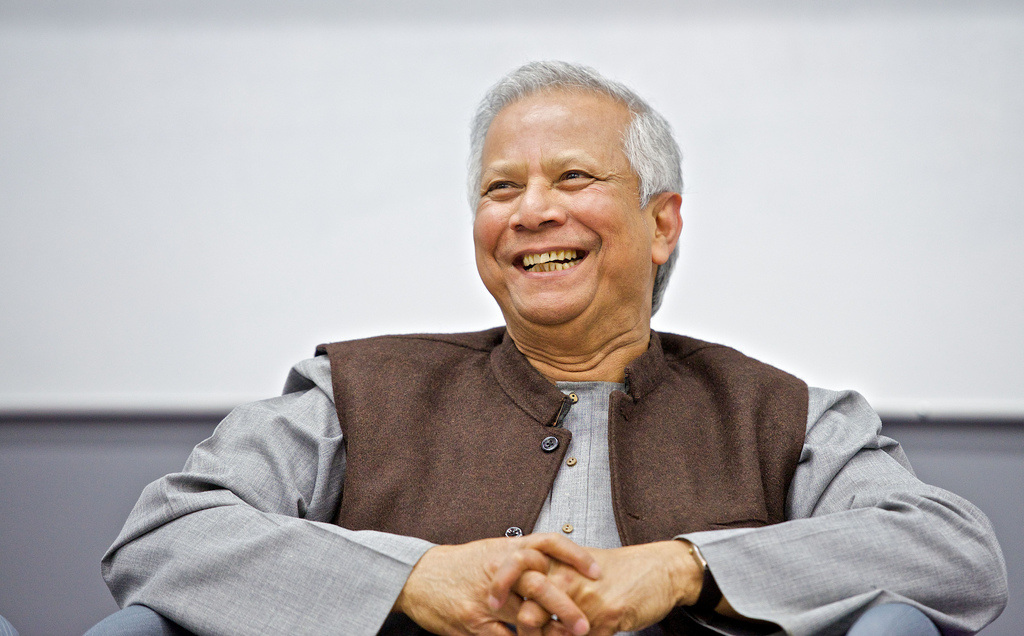

| WASHINGTON — Just a few days shy of his 75th birthday, Muhammad Yunus talked last week about how “Poverty should be in a museum,” and how he intends to put it there by 2030. It was the kind of rhetoric Americans are used to hearing from politicians looking for just the right sound bite to make the 6 o’clock news. And it didn’t help that he said it as part of a speech in Washington, just a few blocks from the Capitol. |

| | End poverty? Yeah, we’ll be sure to pencil that in right after we balance the federal budget and retire the national debt. Except that when Muhammad Yunus says it, even E.F. Hutton ought to shut up and listen. That’s not just because Yunus is one of only seven people who have won the Nobel Peace Prize, the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It’s because his ideas work. E.F. Hutton, the brokerage firm made famous by television ads in which the mere mention of its name made people stop talking and listen, was gobbled up long ago by mergers. Yunus’ ideas just keep growing and multiplying. They aren’t designed to make the rich feel comfortable, however. Yunus is the father of microcredit, the idea that you can give extremely small loans to the poorest people on earth, put them in support groups that help them become entrepreneurs, and turn their lives around. He founded a bank on that principle, and it now has $1.5 billion worth of these small loans. More importantly to Yunus, it has more than that in savings, often from one penny at a time. But people who change the world seldom do so by letting the establishment relax. Microcredit, despite its detractors, is the touchy-feely part of Yunus’ plans. To succeed, Yunus wants to turn the business world on its head. “The present economic system is not working,” he said. “It’s based on a selfish model.” That model assumes that humans are motivated to innovate and trade only by their own desires to become rich. “Wealth is concentrated in a few hands,” he said. “The system pushes it that way.” His solution begins with what he calls social businesses. These exist to make a modest profit while also solving social problems. Investors get only their investment back, along with a feeling of satisfaction. He has used this principle already to provide nutrient-rich foods to the poor, ending diseases such as night blindness, and to provide electricity and cellphones. He longs for a day when innovators create technology for the sole purpose of solving social problems. I have spoken with and written about Yunus often. His success stories resonate with the Western ideals of bootstrap prosperity and the desire to lift others. He is one of the few 75-year-old people I have met who seem to be gaining energy. He isn’t interested in retiring, but he is interested in using social business models to provide pension accounts for the poor, along with housing loans and health insurance. His strongest calling card is his success so far. In 2005, the United Nations set a goal to cut extreme poverty in half by 2015. Bangladesh, Yunus said, achieved that goal in 2013. The advocacy group with which Yunus is closely aligned, called Results, has been working on ways to reduce preventable childhood deaths worldwide through inexpensive vaccines and medicines. In 1990, 12.6 million children in Third World countries died from these preventable diseases. This year, the projected number is 4.2 million. The number zero is in sight, and the nations benefitting are gradually assuming the costs of these drugs. When children stop dying, people begin turning their attention to prosperity, and with microcredit and similar programs, they can see the way to improved lives. It doesn’t take a genius to understand how this makes the world a safer place. And now the U.N. is poised to set a goal, at his urging, to eliminate extreme poverty from the planet by 2030. Will Americans give up notions of becoming rich in exchange for the good feelings they get helping the poor? It’s hard to imagine, but given the positive trend lines in the world, you may not want to bet against Yunus. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed