| When Salt Lake Mayor Ralph Becker, a Democrat, talks about his city, he sounds a lot like Gov. Gary Herbert, a Republican, talking about the state. Success, as the saying goes, has a million fathers. And both the city and state are swimming in it. Gallup recently ranked Salt Lake City No. 1 in the nation for job creation. Forbes pointed to the quality of life, economic diversity and access to nearby mountains when it called the city, “the next national hotspot.” Google brought its fiber network |

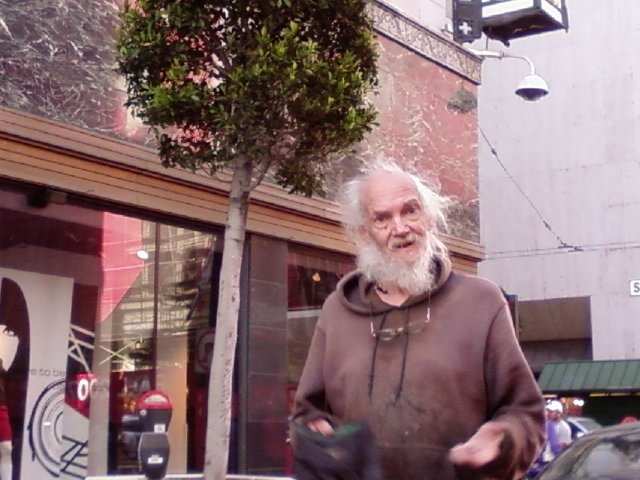

| | to town. And, his honor says with a tone that suggests he knows journalists who have followed the city for decades will be surprised, building permits are at an all-time high. Last year they exceeded $1.8 billion in value, and through four months this year the total already is $1.4 billion. But even hotshot cities have their problems, and in Salt Lake City one of the big ones is panhandling. Try walking a block downtown without being asked for money. Becker is hardly the first mayor to grapple with this. The solution, touted by several mayors and advocates for the poor, is to simply stop giving. But that’s a difficult strategy in a city and state known for its charity. Some may be inclined to see irony here. Among its many accolades, Salt Lake City has been touted recently for reducing its number of chronically homeless people by 91 percent over 10 years. But Becker is quick to say there is no inconsistency. “Most of the panhandlers are not our homeless population,” he said. “They come in every day, establish themselves in a spot, and then when they get enough money they go home again.” The public seems to be aware of this. A recent opinion poll by Dan Jones & Associates, commissioned by Utahpolicy.com, found that 62 percent of city residents would like to see panhandling outlawed. As Becker is quick to point out, that would be impossible. People have the right to ask each other questions without being arrested. But if panhandling is a business, of sorts, it operates on the same principles as any other business. To keep customers coming, salesmen and women have to know which angles to pursue and which buttons to push. As with many of you, I’ve seen my share of gallant efforts. Some try humor. The bedraggled man I saw downtown awhile back held a sign saying, “For every dollar, a Justin Beiber fan dies.” A woman who stopped me one day told me a lame “blond” joke before asking if I could help a struggling comedian find better jokes. And one particularly nasty panhandler used to sit on a corner near my office shouting insults to people who didn’t give him money. A colleague of mine who is bald except for a strip of hair around the sides was told he had a Bozo the Clown haircut. I was told, one Halloween, that my clothes were a “nice devil’s costume.” Others feign friendship, like the elderly couple who made pleasant small talk on TRAX one day until I agreed to give them some change, then quickly left me like a discarded cigarette and began making small talk to someone else. Experiences like these make for interesting stories at parties, but they are not great for attracting shoppers from the suburbs. The mayor notes that red meters throughout downtown are receptacles for donations to shelters. He also would be eager to work with the City Council on an ordinance to address aggressive panhandling. But he acknowledges the problem is complicated. It’s just complicated enough that panhandling is likely to remain a part of the downtown experience for the foreseeable future. After decades of fruitless efforts, this seems to be an inescapable reality. In truth, that isn’t the worst that can happen. People can benefit from peaceful encounters with the destitute, even if the destitute aren’t as destitute as they seem. There is something healthy about reminders of our own tenuous place in the world, even if it’s inconvenient. As the mayor, governor and other politicians probably would agree, it hardly lowers the temperature of a national hotspot. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed