| Whenever I attend State Department briefings for editorial writers in Washington, this question inevitably comes up: Why does the United States feel the best way to influence democratic change in China is to maintain diplomatic relations and trade, while the best way to do the same in Cuba is through embargoes and no official relations? Through the years, the answers haven’t varied much. First, as a Bush administration official told us years ago, you shouldn’t expect those kinds of consistencies in foreign policy. Each nation presents a different set of circumstances and history. Second, Cuba is 90 miles from our shore, which makes the presence of a communist dictatorship a special case. |

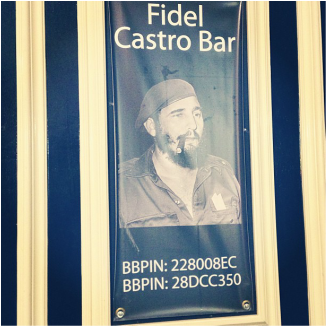

| | What they generally never talk about are the electoral votes in Florida, which is a key state for any presidential aspirant. Florida is home to a vast population of Cuban ex-patriots who are loud in their defense of embargoes and strong in their hatred for Fidel and Raul Castro, and they vote. Against that historical backdrop, President Obama’s decision to begin the process of restoring diplomatic relations, establishing a U.S. embassy in Havana and suggesting an end to the long embargo, was curious. Perhaps only a lame-duck president just past his final mid-term election challenge could do such a thing. On Wednesday, the president declared the nation’s half-century-old policy of isolation a failure, which is true if the only definition of success is a regime change. Obama called the policy a rigid one “rooted in events that took place before most of us were born.” And yet the Castro brothers remain as entrenched, if aging and stooped, as they did when the policy began. Since the president brought up the subject of being born, it is significant to note that on the day I was born the New York Times featured a front page photo of Fidel Castro, dressed in army fatigues, being greeted in the United States by President Eisenhower’s acting Secretary of State, Christian A. Herter. I am not a young man. Castro was on an 11-day tour of the United States. This was before relations went terribly wrong; before the botched Bay of Pigs invasion, the Cuban missile crisis, the Mariel boat lift and decades of animosities. However, it may not have been before the start of Castro’s human rights atrocities. Aggressive interaction with American wealth, tourism and business may indeed be a better policy for shaking loose a repressed populace, but the United States should never forget exactly who it is they are dealing with in Cuba. A State Department human rights report puts it in clear language. The regime’s human rights abuses include “beatings, harsh prison conditions, and selective prosecution and denial of fair trial.” During the period studied for the report, “Authorities interfered with privacy and engaged in pervasive monitoring of private communications. The government also placed severed limitations on freedom of speech and press.” Obama’s announcement was preceded by Cuba’s release of Alan P. Gross, a contractor who, illustrating the report’s accuracy, was imprisoned for five years because his delivery of satellite telephone equipment to the island was seen as a plot to “destroy the revolution.” Americans cannot afford to be as naïve as Rep. Barbara Lee, who said after meeting with Fidel Castro in 2009 that he was “clear thinking.” Nor should they be like her equally smitten colleague Rep. Emanuel Clever of Missouri who described him as “one of the most amazing human beings I’ve ever met.” The danger, of course, is that U.S. trade will enrich the thugs who run the country, while poor and needy families continue in poverty. Yes, a half-century of isolation has failed, but there may have been other reasons for it than only the hope of influencing regime change. If Congress approves a lifting of the embargo, my colleagues will have one less question about inconsistent foreign policies to ask at the next gathering in Washington. Free trade tends to benefit all involved. Havana may become a tourist destination once again. Dictators, however, seldom relinquish power or change behavior because of U.S. policies, and there is little reason to believe renewed relations with Cuba will be any different. After all, open relations haven't changed China's leadership. Neither has Cuba's relationship with other Western countries. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed