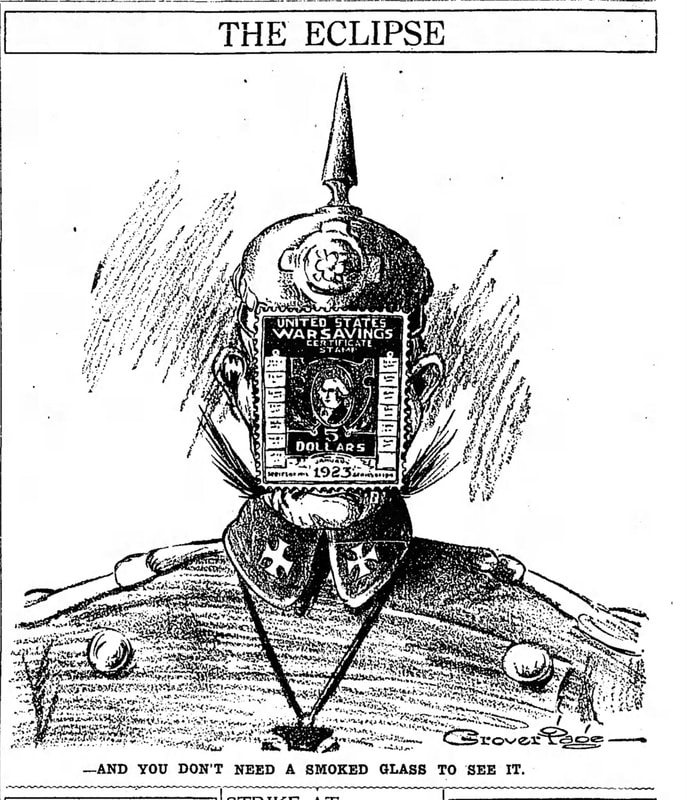

| Hotels and motels are booked solid for Aug. 21 along the path of the first total solar eclipse to cover much of the United States in 99 years. The Guardian reports, “Never will a total solar eclipse be so heavily viewed and studied or celebrated.” That statement may be impossible to prove, but it is undeniable that unprecedented mobility, peaceful times and a good economy are combining to allow Americans to flock to the affected areas as never before. That doesn’t mean Americans didn’t care about the eclipse that crossed the continent on June 8, 1918. Many newspapers from coast to coast reported on the event, but not all. Those in areas not along the path of eclipse tended not to mention it. And even in places along the direct path, the |

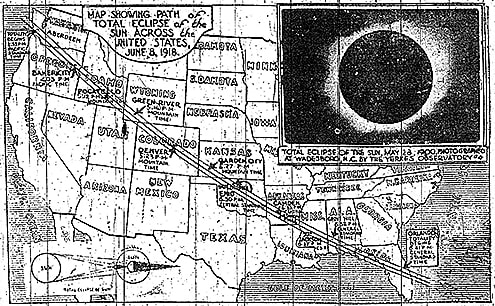

| | eclipse was overshadowed (pun intended) by a world at war. American troops were advancing in France. Before one counter attack, German forces fired gas bombs that formed dark clouds, one paper reported. It’s hard to get too worked up over an eclipse when a father, brother or son was in the middle of the fight “over there.” And yet hundreds, if not thousands, of people headed to parts of Oregon and Washington, where the eclipse hit the continent first and lasted the longest. Government astronomers headed to Baker, Ore. United Press detailed the plan. “As a stout-voiced sailor from the Bremerton naval station calls off each second of totality, each member of the government party will perform his allotted task.” That included the taking of 50 photographs, using black-and-white film, of course, and some motion pictures. An artists was on hand to paint a color rendering of what he saw. Locals armed themselves with “bits of smoked glass, and will make their own observations, unhampered by the necessity of obtaining records.” The news service said the narrow band of the total eclipse “was the mecca of thousands of tourists.” That was supposed to be an important eclipse, as scientists were trying to prove Albert Einstein’s theory that space is curved by mass. The eclipse would allow them to view stars during the day, seeing how much the sun’s gravity pulled on those rays of light. Unfortunately, a thin layer of clouds appeared at just the wrong moment, making it impossible to make such an observation. Confirmation of Einstein’s theory would have to wait until 1919, when teams of scientists observed an eclipse in South America and Africa. Denver offered another great vantage point in 1918. The International News Service said, “Every mountain peak in the Rockies lying to the west of the city is the temporary rendezvous of men of science. Every sizeable telescope obtainable has been carried to some point of vantage in the thin air of the mountain tops from which professors from virtually every college in America will observe and endeavor to photograph the phenomenon.” There, too, clouds ruined the day. Scientists had little to do but sit back and observe the colors of the clouds as day changed to night and back again. None of the news stories I found mentioned anything about accommodations for the tourists. People were hardy back then. I imagine a lot of bedrolls were used on the ground. In many ways, much has changed in a century, and overwhelmingly for the good. That may be worth pondering, as well, as the relatively rare event of Aug. 21 approaches (another one will hit the U.S. in 2024). Our ancestors would be envious of our relative peace and unfathomable prosperity. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed