| I have a strange relationship with the Spanish Flu pandemic that killed, by some estimates, 50 million people 100 years ago. If it hadn’t occurred, I wouldn’t be here. My Norwegian grandmother came to Salt Lake City near the start of World War I. Some of her friends had come here years before and urged her to |

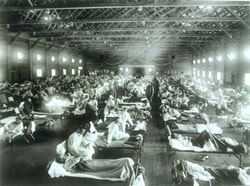

| | follow. I’ve seen the postcards they sent her, complete with pictures of people floating off the shores of the old Saltair amusement park, the long skirts of their swimsuits billowing in the wind. To support herself, she became a maid at the old Hotel Newhouse downtown. But she never liked it, and she longed to return home. She developed a relationship with a wealthy Norwegian man who said he would take her home if she would marry him. She consented. They went back to Norway. In 1918, the Spanish Flu hit that country just as it did much of the world. Her husband contracted it and died. A while later, she met the man who became my grandfather. But while I enjoy pondering this connection, it doesn’t make me partial to pandemics. We can't change history. For one thing, it might result in my sudden disappearance. But we should be more prepared for the future. News stories already are pointing to a harsher-than-usual flu season. Australia, which gets the jump on each year’s new mutation of the virus, found that this year’s vaccine — an annual shot at a moving target — was only about 10 percent effective. In Northern Ireland last week, churches announced a suspension of “the customary sign of peace handshake” that parishioners traditionally exchange during mass. That’s a far cry from a century ago when the Salt Lake County Commission ordered all public buildings closed, including churches, theaters and schools. On Armistice Day, as on Election Day, people had to decide whether patriotism was more important than the risk of dying. Ever since, public health officials have been quick to sound alarms whenever a hint of pandemic is in the wind. In 1976, President Gerald Ford started a nationwide inoculation program against a swine flu epidemic that never came. Some people became horribly ill because of the vaccine. More recently, scares involving strains of avian-borne viruses have induced mild panic. But just because the world has not experienced a flu pandemic similar to the one a century ago doesn’t mean it can’t happen again. Nor does it mean we’re ready. An op-ed in the New York Times on Tuesday, co-written by the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, outlined our desperate situation. “We are not prepared,” he said. “Our current vaccines are based on 1940s research.” These would be as effective against a pandemic as “trying to stop an advancing battle tank with a single rifle.” He recommended a national strategy, complete with adequate funding, to develop a universal vaccine against all strains of influenza A — something the National Institutes of Health has made a priority. While he didn’t mention it, governments from Washington to the smallest towns also ought to have plans in place for handling an outbreak. One hundred years later, it’s hard to imagine what the world endured. In his thoroughly readable book, “The great influenza,” John Barry describes how the dead overwhelmed government institutions in Philadelphia and elsewhere. Bodies were buried without coffins. At its peak, the flu killed with amazing quickness. Barry cites an account by Charles Lewis in Cape Town, South Africa. He jumped on a streetcar for a three-mile ride “when the conductor collapsed, dead. In the next three miles six people aboard the streetcar died, including the driver.” To be sure, we won’t see that this year, although it is sobering to note that the flu kills an average of 36,000 people in the United States each year — a number that would alarm us if it were caused by a new disease. I stop short of saying I’m grateful for the pandemic that made my life possible. I also don’t know what strange quirks of history may influence future generations. But I do know one thing. If scientists believe it’s possible to eradicate the flu, creating a vaccine ought to be a national priority. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed