Having survived a year in which the nation’s future seemed to teeter between two polar-opposite presidential contestants; when random mass murders went from the unthinkable (opening fire on a crowded movie theater) to the unspeakable (killing kindergarten students and their teachers); and when elected leaders ended the year with a seeming eagerness to throw Americans off

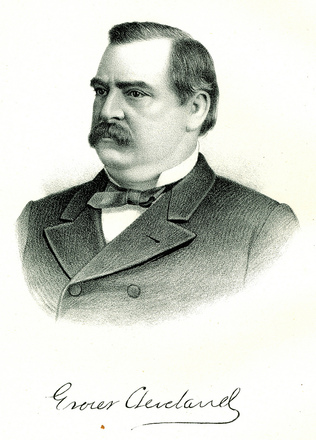

| | something called a “fiscal cliff” — writing New Year’s resolutions may seem about as important as straightening paintings in a burning house. And yet, people will be dancing in Times Square and at countless other parties Monday night, professing optimism for the new year. This is not a sign of incurable stupidity. We don’t approach the future like subjects in some morbid experiment who insist on doing the same things over and over, hoping for a different result. We are, speaking of humanity as a whole, creatures of incurable optimism. Good thing, that. Every rearview mirror comes with a switch that allows you to view the same receding landscape without so much glare. The media, present company included, tends to ignore that switch. Only when confronted with faith, optimism and forgiveness in the face of tragedy, or joy at the start of a new year, do they confront a strange world where not everyone judges life in terms of headlines. A trip to the past illustrates this perfectly. One hundred years ago today, the nation was emerging from a bitter presidential race. You think 2012 was contentious? In 1912, a charismatic former president, Theodore Roosevelt, rocked the Republican Party by defecting to run as a third party candidate. That paved the way for the election of a Democrat, Woodrow Wilson, who remains a divisive figure a century later. Progressives and conservatives were waged a bitter contest. Two constitutional amendments would take effect in 1913, dramatically altering the nation’s future. One legalized the federal income tax, allowing Congress to tax the rich. The other made senators elected by popular vote, rather than by their state legislatures. On New Year’s Day in 1913, the Wall Street Journal published a report from Darwin P. Kingsley, president of the New York Life Insurance Co. Speaking of the recent election, he said the growth of socialism was the greatest threat to the nation. Bitter labor strikes threatened to rend the nation. The end of 1912 saw the final sentences handed down in a case in which labor leaders had set explosives at various places around the country. In the worst of these, bombs were detonated beneath the Los Angeles Times building, killing 21 and injuring 100 more. The Times had published editorials against labor organizers. Any of these events easily match whatever happened in 2012. And, by one view of the mirror, things quickly got worse. Before the decade was out, the world had been engulfed in war and an influenza pandemic had wiped out tens of millions of people worldwide. And yet one of the most interesting stories of a century ago is a little blurb in the New York Times. It concerns a horrible accident at a holiday party in the Illinois home of a former U.S. vice president. A 12-year-old boy, perhaps mimicking the drill a young military academy student had just performed to impress the girls, discharged what he thought was an empty gun, killing a 15-year-old girl who was a party guest. The young shooter’s name was Adlai Stevenson. He was, by reports at the time, inconsolable. Yet years later he was governor of Illinois and the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Twice he ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate against Dwight D. Eisenhower. Stevenson was known for his strong advocacy of peace and his frequent self-deprecation. Historians have speculated that the accident molded his character. Regardless, he clearly chose to remove the glare and move ahead with optimism. So did the nation as a whole. Not many people today would enjoy having to live as if it were a century ago, no matter what we may think of the year just ending. We move forward with resolve, knowing we can indeed make things better. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed